“Whatever inspiration is,

it’s born from a continuous ‘I don’t know.’”

— Wislawa Symborska

When I was thinking about the novel that would become “The Shelter of Each Other,” several things happened out of the blue.

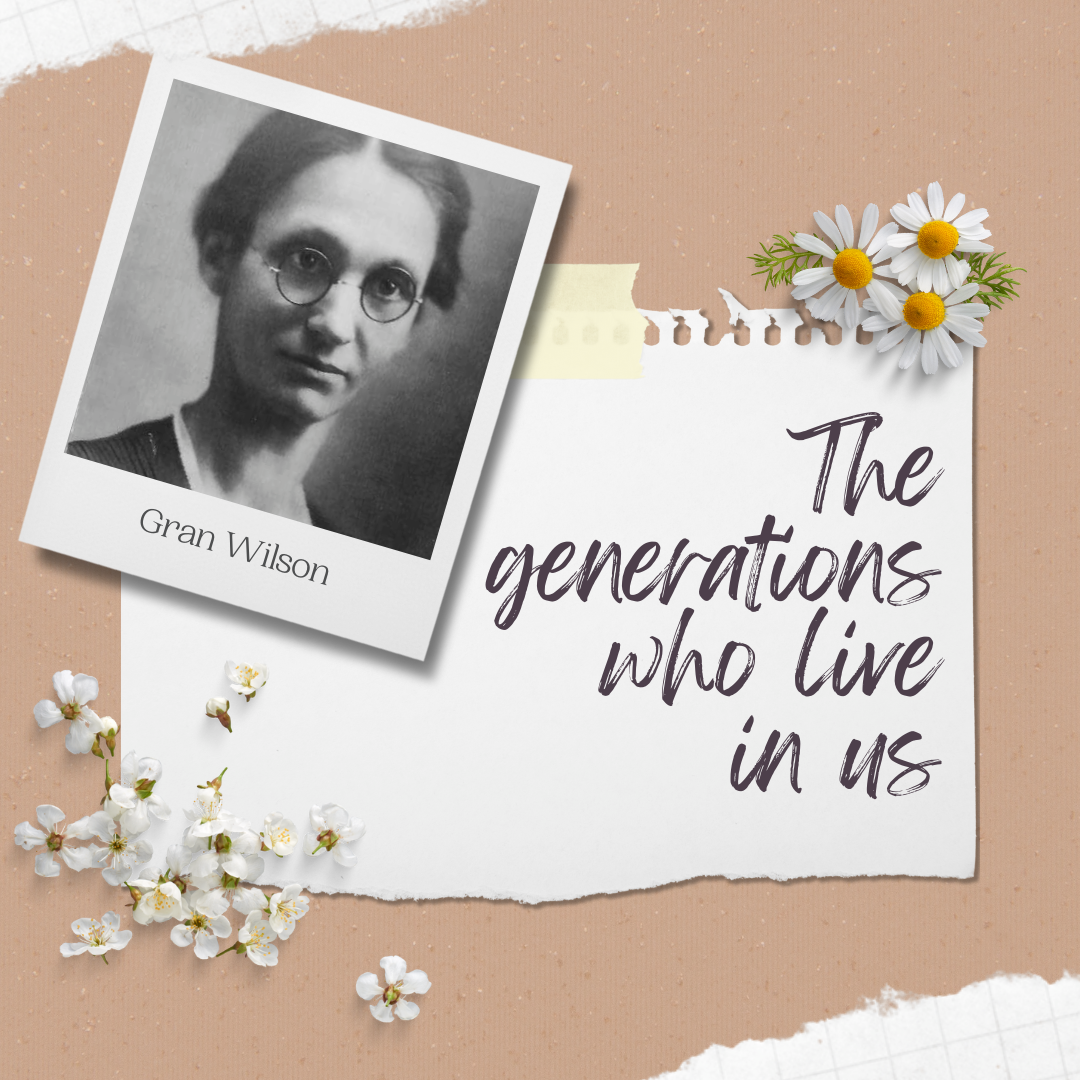

My paternal Grandmother, Gran Wilson, drifted into view. I started looking for her on Ancestry.com and instead of reading only information about date of birth, date of death, I decided to dig further. To my wonder I rediscovered the family that, for all these years, I believed had been her adoptive family. While they did eventually adopt her, at eleven years old, she was actually a domestic in that household.

The story of Bridget Blackwell is not my Gran’s story, yet she came into view in the same way this detail of my Gran’s life appeared. The unknown became the known — a little girl living on a farm, apparently as a domestic, without family of her own. I put together some of what I was learning about Gran’s life. Born in 1880, she was a domestic at 11, a mother of four children by the time she turned 26, and a widow at 36. She was a woman who wrote on her marriage certificate, by parents’ names… ‘don’t know..’ Was she the seed of inspiration that revealed a ten year old Bridget ?

Do I know the answer to that question? Not in truth. But I do wonder — if I’d never brought to light the uncovered fragments of Gran’s story, would Bridget’s story be different? Would there have even been a Bridget?

Inspiration? Gran? Maybe.

Or was Bridget and her story already there, waiting?

In whatever manner she appeared into my life, the inspiration which gave her life is a mystery. Rather like the act of writing.

As an author of fiction and as an inveterate storyteller, I know that stories are like gossamer. They are made up of ideas emerging from my experiences, threads of possibilities. And yes, imagination.

Brenda Ueland writes that “Imagination sometimes works slowly, quietly.” My italics.

I was well into the story of Bridget’s unfolding life when I realized my longing to tell her story could be a generational longing emerging from the dreams and hopes of my eleven-year-old Gran.

When does inspiration happen?

Slow down,

(Riffing on Mary Oliver*)

pay attention,

be brave.

Write about it…

*Instructions for living a life:

Pay attention. Be astonished. Tell about it.

Excerpted from the poem: Sometimes. Red Bird. Boston, Beacon Press, 2009 p.37

An important character in The Shelter of Each Other is Sophie Watson. She represents the “wise person” I choose to believe we have in all of us. Sophie takes on the promises that each woman, openly or silently make to one another. In many ways she is the promise of constancy throughout the unanticipated and the stunning events that life offers up.

An important character in The Shelter of Each Other is Sophie Watson. She represents the “wise person” I choose to believe we have in all of us. Sophie takes on the promises that each woman, openly or silently make to one another. In many ways she is the promise of constancy throughout the unanticipated and the stunning events that life offers up.